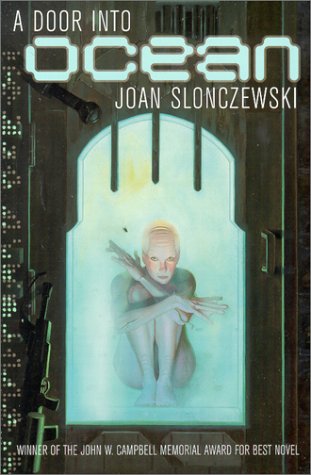

I picked up A Door Into Ocean (1986) because I wanted something completely different from the Song of Ice and Fire books. A Door Into Ocean is science fiction, not fantasy. It’s mostly set on a planet that’s all water, where all the (human-descended) inhabitants are female and purple and peace-loving. It has spaceships and planets and sort-of aliens—actually a lot of the book is about the alien-looking people trying to decide whether the human-looking people are really human. Yet it does have some things in common with the Martin—both share a strong sense of how history shapes the present and the way people’s virtues are as likely to cause them problems as their flaws.

A Door Into Ocean is set a long time in the future. There was a galactic empire that collapsed in war a thousand years ago, and there used to be a thousand inhabited planets, many of them terraformed. Now there are 93 inhabited planets, and there’s slow FTL connecting them. Atomic manipulation and genetic engineering are both forbidden. Because FTL is slow, control over the planets is tenuous, an Envoy from the Patriarch visits every nine years to make sure all is going according to plan. Valedon and Shora are both inhabited and both in the same system—Shora is Valedon’s “Ocean Moon,” it has no land, and the inhabitants live on rafts. Valedon has been part of the Patriarchal system all the time, Shora has spent a thousand years ignored, with a constant population of less than a million living at a very low tech level. In the last generation Valedon has come into contact with Shora again, and their different ways of living bring them into conflict. The inhabitants of Shora call themselves “Sharers” and chose names that commemorate their worst flaws they need to live down. The inhabitants of Valan live in castes, have armies, and don’t share anything.

What I remembered best about this book was the way the Sharers live in on floating rafts as part of a huge complex network of genetically engineered communication devices, and how their reaction to anything new is to learn about it, and the worst punishment they know is “Unspeaking”: cutting off communication. Their way of life is very unusual and memorable—and their tactics for dealing with the invasion of Valan traders and then soldiers would have been familiar to Gandhi. They have genetically engineered themselves to be all female, to have purple skins for better oxygen retention under water. They have genetically engineered everything around them to suit their way of life. They look to the Valans and the Patriarch’s Envoy as if they have no technology, while in fact their technology predates and outstrips everything. They worry about seeing themselves clearly and naming themselves and sharing responsibility for their children and their planet.

This is the story of how Shora defeats Valedon and the Patriarchy, despite the other side appearing to have all the advantage. It’s also the story of how Spinnel, a poor boy from Valedon, grows up and comes to know himself. The technique of showing us Shora through the eyes of someone for whom it’s all strange works well, and the ways in which Valedon and Spinnel’s expectations are strange to us makes it more interesting. The war, and the non-violent non-resistance, go much as you would expect—the interaction of people and cultures is what makes it good. Maybe the Sharers are a little too perfect in their self-naming and sharing, and the Valans a little too patriarchal for subtlety—but the existence of stone addicts and murderers among the Sharers, and the complexity of the Valan characters who come to Shora, Nisi the Deceiver and Spinnel, more than compensate. The Shoran point of view characters, Merwen and Lystra, are interesting and complex, but Nisi and Spinnel have to come to terms in their different ways with a way of life that isn’t axiomatic for them. A lot of what makes this compelling is the choices they make as they move across cultures.

A Door Into Ocean won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for hard science fiction, and was nominated for the Prometheus Award for libertatian science fiction. It’s a good choice for both of them, but a surprising choice too. This is a quiet book where most of the science is traditionally neglected and disparaged lifescience—neglected not just by the Valans but by the people who usually define hard SF. And while the Sharers are definitely opposed to an authoritarian system, they’re definitely not Libertarian—their system is more like family socialism spread across a moon. I was surprised it hadn’t been Tiptree nominated, because it definitely is doing interesting things with gender, until I remembered that it came out in 1986 and the Tiptree Award didn’t start until 1992.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.